ENGLAND: THE OTHER WITHIN

Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Ethiopia in England

Christopher Morton

Head of Photograph and Manuscript Collections

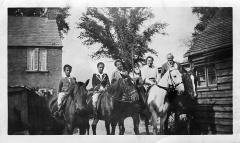

2008.1 James Duck, his wife, and the 3 Ethiopian children, on horseback in the yard of Duck's stables.

This photograph was donated by me on behalf of my family to the Pitt Rivers Museum in January 2008 specifically as a result of having been asked to write a short biography about one of the Museum's 'English' photographs. In part I have chosen it in order to highlight the difficulty of defining what an 'English' photograph is, but also since it encapsulates a range of issues concerning British cultural and political identity in the period.

During the course of discussions with colleagues working on The Other Within project, it soon became apparent that the working definition of 'English' photographs was going to be narrowly defined for the purposes of the project to only those taken in England. The restriction to 'images of England' rather than 'images of Englishness' means that I am unable to discuss what was my first choice for a biography, a photograph by anthropologist Godfrey Lienhardt of his student Jean Buxton sitting in a camping chair at a picnic table, complete with gingham table cloth, under a large tree in southern Sudan. The perfect re-creation of a summer's afternoon in Oxford in central Africa.

Co-incidentally, the image that I have chosen to discuss here is one of Africa-in-England rather than England-in-Africa. The photograph shows my great-grandfather James Duck, his wife, and three Ethiopian children, all on horseback in the yard of his stables off the High Street in Marlborough.

1998.97.571 Jean Buxton sitting at a picnic table in the shade of a large tree at Gogrial, Southern Sudan

The boy on the left is Prince Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie (1931-1962) who was the youngest son of Emperor Haile-Selassie.

The boy in the middle is Lij Ameha Desta (1928-1944), the son of Princess Tenagne Worq Haile-Selassie (Haile-Selassie's daughter, 1912-2003) and Ras Desta Damtew (who remained in Ethiopia to resist the Italian invasion, but who was captured and executed in 1937). This boy, Lij Ameha Desta, unfortunately died shortly thereafter in Bath in 1944 at the age of 16.

The girl on the right is Princess Aida Desta the sister of Lij Ameha Desta, who is still alive and was able to provide me with the identifications.

The photograph was taken sometime during Emperor Haile Selassie's exile in Bath between 1936 and 1941, but presumably early on in that period, since Aida Desta has suggested that Prince Sahle-Selassie may have attended Marlborough College for a short period (where James Duck acted as Riding Master) before going on to attend Wellington College. 1

The photograph shows the three exiled children, dressed in public school attire, in a relaxed and happy moment, about to embark on a ride along the fields and lanes above the town.

Because of its apparent informality, the photograph is all the more redolent of the particular sets of historical colonial relationships that resulted in Haile Selassie's decision to seek exile in England. Apparently exile in Switzerland had been suggested, but the condition of not engaging in political activity was unacceptable (Haber 1992), especially since the Emperor's main aim was to lobby support from the League of Nations against the Italian invasion. Some have seen the invasion of Ethiopia as the first conflict of the Second World War, a perspective that gives this image of exile in England, taken a few years before its official outbreak, an added sense of tension.

From this perspective, these three children gathered in a Wiltshire stable yard are exiles from the frontline of an approaching international conflict that only a few could foresee. Their apparent comfortableness in the situation bespeaks of the sort of British colonial and cultural influence that was widespread amongst the world's elite in the period. The vision of England as a place of peace and security encapsulated in this image is one particularly activated by the identity of the children and the historical and political events that they are caught up in. On the one hand, these intertwining historical contexts all generate a complex set of meanings for this image, centred upon a vision of England at ease with itself, sure in its colonial identity and strength. On the other hand, it is an image of people thrown together as a result of the fragility and instability of world events. And yet this image captures a moment between these contradictory tensions, showing children enjoying the moment, not thinking of the rapidly-changing world outside a Wiltshire market town.

The smiling paternalism of James Duck and his duty of care toward his royal visitors seems to echo the paternalism of England towards its colonies (although Ethiopia was of course not one), a set of political and cultural attitudes that would change irrevocably over the next two decades. Somehow this vision of Africa-in-England conjures up something very particular about Englishness as an international identity, rather than one necessarily contained by these shores, and one that is constantly in flux. It is an image that shows how Englishness as an imaginative construction has often come from outside, and how its values and identities have often been historically negotiated against the backdrop of world events.

Note

- Personal correspondence from Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie, 2-8 May 2006.

Reference

Haber, Lutz, 1992. The Emperor Haile Selassie I in Bath 1936-1940. Occasional Paper of The Anglo-Ethiopian Society.