ENGLAND: THE OTHER WITHIN

Analysing the English Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Calendar-related objects

Spring-time, planting and Easter.

Alison Petch,

Researcher, 'The Other Within'

Most people who live in Northern Europe find that their spirits are raised when the long winter ends; days become sunnier, longer and warmer; birds twitter in the trees and vegetation once more starts to grow. This has probably been true for as long as humans have lived in this climate and region. England and the English are no different. There are lots of traditions, customs and artefacts associated with Spring and its associated Christian ceremony, Easter, and this article discusses some of them. According to wikipedia, Spring is often considered to comprise the months of March, April and May in the northern hemisphere. It is the season between winter and summer, when most plants begin to grow.

Easter is the most important festival of the year for the Christian faith. According to wikipedia the egg was the symbol of new life for Christians because it celebrates the central miracle of the faith, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Modern Easter is a movable feast, celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon on or after 21st March. The festival starts on Good Friday, the day associated with Christ's crucifixion, and ends on Easter Sunday, when he was resurrected.

Good Friday

The Friday before Easter Sunday. According to Roud, it has been called Good Friday by the English since at least 1290 AD. Before Bank Holiday legislation of 1871, Good Friday was one of only two days holiday granted to most workers (the other was Christmas Day),[David, please link Christmas Day to the object biography for Christmas] and all shops were shut. [Hutton, 1996:112, 192] It was traditionally a day of fasting and sombreness.

Hot Cross Buns

A hot cross bun is a sweet spiced bun leavened with yeast and added dried fruit. It has a cross on the top made from pastry, rice paper or cut into the bun. This symbolised the crucifixion. It was traditionally eaten on Good Friday, the first recorded use of the term 'hot cross bun' was not until 1733 according to wikipedia. Today, in the UK, hot cross buns are available for purchase in the shops most of the year, and most people eat them spread with butter.The hot cross bun [1981.11.2 illustration] in the Museum collections was donated by one of the original directors of this research project, Dr Hélène La Rue (who recently sadly died). It is described as follows in the accession book:

ENGLAND. A hot cross bun made by donor on Good Friday before 12 noon, 1976. Grated & mixed with a hot drink to cure colds (this is the London belief - for other regions see Related Documents file). It is believed that if made before 12 noon on Good Friday it will never decay.

Hélène made and donated this object early on in her career at the museum, but she had always been interested in English folk customs. She must have been right about buns being made on that day not decaying as some 31 years later, when this photograph was taken of the bun, it looked in remarkably good preservation. It has been suggested that it was believed that bread baked on Good Friday was considered to have excellent medicinal and protective properties, [Roud, 12007:108] and this obviously fits with Hélène's belief that it could cure a cold. Hutton remarks:

'During the nineteenth century, across virtually the whole of England, and in parts of Wales, folklorists discovered the superstition that bread, buns, or biscuits baked upon this day had especially beneficial powers. They were generally believed never to go mouldy, and to be capable of curing diseases, especially intestinal disorders, if eaten. If hung in the house, they were thought to protect against it against misfortune. Not merely the day of manufacture was important, for like a pre-Reformation host they had to be marked with the sign of the cross. ... By the nineteenth century, these special pieces of bread werfe known very widely by the name of Hot Cross Buns, and they survived as the traditional Good Friday morning or midday dish in areas where their magical qualities had been forgotten, and they had become commercialized' [Hutton, 1996:192-3]

Hot cross buns are commemorated in a nursery rhyme:

Hot cross buns,

Hot cross buns,

one ha' penny,

two ha' penny,

hot cross buns.

If you have no daughters,

give them to your sons,

one ha' penny,

two ha' penny,

Hot Cross Buns.

It has been suggested that this nursery rhyme is based upon street vendors' calls and that it dates to before 1733. [Hutton, 1996:193] According to the wikipedia entry for Hot Cross Buns which includes the rhyme:

There are two versions of the tune. The simple version is played with the sequence A,G,F whilst the original more musical version uses the notes A,A,D, where the second A is one octave lower than the first.

Recipe (N.B. we do not know that this is the same as the recipe used by Hélène La Rue to make the museum artefact!)

Recipe taken from the BBC food website (http://www.bbc.co.uk/food/recipes/)

Ingredients (for 12 buns)

For the ferment starter:

1 large egg, beaten

215ml/71?2fl oz warm water

15g/1?2oz fresh yeast

1 tsp sugar

55g/2oz strong white flour

For the dough:

450g/1lb strong white flour

1 tsp salt

2 tsp ground mixed spice

85g/3oz butter cut into cubes

85g/3oz sugar

1 lemon, grated, zest only

170g/6oz mixed dried fruit

2 tbsp plain flour

oil, for greasing

1 tbsp golden syrup, gently heated, for glazingMethod

1. Prepare the ferment starter for the dough by combining the beaten egg with enough warm water to give approximately 290ml/1?2 pint of liquid. Whisk in the yeast, sugar and flour, cover and put in a warm place for 30 minutes.

2. make the buns: sieve the flour, salt and spice into a large mixing bowl and rub in the butter. Make a well in the centre and put the sugar and lemon zest in the well. Pour on the ferment starter.

3. Gradually draw in the flour and mix vigorously, then knead to a smooth, elastic dough.

4. Carefully work in the mixed dried fruit. Shape the dough into a ball, put it in a warm, greased bowl, cover with a clean tea towel and leave to rise in a warm place for 1 hour.

5. Turn out the dough and knead to knock out any air bubbles and give an even texture. Shape it into a ball again, put back into the bowl, cover and put back to rise for another 30 minutes.

6. Turn out the dough again and divide into 12 even pieces. Shape them into buns and leave to rest for a few minutes on the work surface covered with the tea towel.

7. Place the buns on a lightly greased baking sheet. Slightly flatten each bun and then cut into quarters, cutting almost all the way through the dough, so that as each bun rises, it has a well-marked cross on it.

8. Grease a large polythene bag and place the tray with the buns in it and tie the end. Put in a warm place and leave to rise for 40 minutes.

9. Meanwhile, heat the oven to 240C/475F/Gas 8. Make a paste for the crosses on the buns with the plain flour and 2 tbsp cold water. Mix until it is soft enough to pipe through a nozzle.

10. Remove the polythene bag and pipe a cross on each bun. Bake the buns for 8 -12 minutes or until risen and golden. Brush the buns with hot golden syrup as soon as they are ready. Cool on a wire rack.

There are supposed to have been attempts to ban the sale of hot cross buns, because they might offend people with religious beliefs other than Christianity. See, for example: the report in the Daily Telegraph by Chris Hastings and Elizabeth Day on 15 March 2003, entitled 'Hot cross banned: councils decree buns could be 'offensive' to non-Christians'. Upon closer inspection, many such stories turn out to be exaggerations or untrue (see, for example, the article 'The phoney war on Christmas' by Oliver Burkeman published in the Guardian on 8 December 2006.

Easter Sunday or Easter Day

Easter eggs are traditionally given (and eaten) on Easter Day. They are specially decorated eggs given out to celebrate the Christian Easter Sunday, in springtime. Eggs have been said to symbolize new life, birth and regeneration. The tradition might have come from the celebrations to end the privations of Lent (when people fasted and eggs were traditionally banned). Other sources suggest that the egg association came about because of the coincidence of Easter generally occuring at the nesting time for most birds. Traditionally dyed and painted chicken eggs were used but now commercially made chocolate eggs are most often given instead. Chocolate eggs are said to have started in mainland Europe during the nineteenth century and spread to England. Depending on which source you rely on either Fry's or Cadbury's developed the first in the 1870s.The Museum's Easter Egg [1970.7.1] is described as:

England, Westmorland, Ulverston. Hen's egg, coloured in various shades of blue, pink, green, yellow etc. Prepared by Mrs Katherine Ovey (neé Fell) on Good Friday 1970 in accordance with the tradition in her Westmorland family who for generations have practiced EGG-PACING at Easter. On Good Friday available members of the family gathered together in Ulverston. With cousins, the company often amounted to about 30. Suitable 'loose-coloured' materials, paper, or cloth or veiling, have been hoarded in a bag through the year by each member of the family in readiness for the ceremony of egg-pacing. Pieces of material are selected, dipped in water and laid on the egg to form a pattern of colours, then the egg is wrapped first in wet linen or cotton rag and then in folds of newspaper, and tied up with string. The head of the household where the gathering occurs places the parcelled eggs in a cauldron or vat of hot water which is kept boiling for 20 minutes. The parcels are then fished out. Those taking part in the ceremony are expected to recognise and claim his or her parcelled egg. The eggs are unwrapped and greased with butter to give them a pleasant shine. Chosen judges decide which is most beautiful and which is the ugliest! At one time ritual games were played with the eggs on Easter Monday. See Christina Hole, English Custom and Usage. B.M.B. [Beatrice Blackwood].

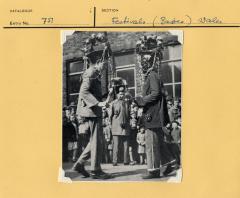

Christina Hole described 'pace-eggs' as 'simply a hard-boiled egg with the shell dyed red or green or yellow'. [1941-2: 48] Pace-egging is described in some detail by Roud [2007:118-120] According to him, it was a specifically Northern English (and Scottish) activity, not encountered in the south of the country. Although the accession book does not record it, other accounts [Roud, 2006; Danielli, 1951] record that egg-pacing often involved the collection of money and visiting houses in the local neighbourhood. The image here shows a cutting from English Dance and Song cut onto one of Mrs Ettlinger's working catalogue cards (now part of the PRM ms and photo collections) showing the Midgley pace-eggers from the Calder Valley in Yorkshire. Danielli says that the eggs used for eggs-pacing in Sawrey, Westmorland, were hard-boiled edggs whose shells had been dyed:

The usual method in the Sawreys is to wrap the eggs in onion skins and either directly tie them or first wrap them in pieces of cloth and then tie them, followed by boiling in water for about fifteen minutes. When finished the eggs come out coloured from yellow to deep brown, often pleasantly mottled or marked with the veining on the onion skins. These eggs are prepared a day or two before Easter, some are taken to neighbours and friends as gifts... [1951, 464]

A variety of egg-connected Easter activites have been recorded including: egg-rolling, bashed together like conkers, decorated and kept for show, or made into special Easter cakes. Any of these activities might be called pace-egging (or peace-egging, pash-egging or paste-egging). [Roud, 2006:118] The various terms were derived from the Latin word paschal.[Hutton, 1996:202]

Roud records that the first mention of egg-decorating occurs in 1778 in William Hutchinson's History of Northumberland: 'The children have dyed and gilded eggs given to them, which are called "Paste eggs". Pace-egging often seemed to involve visiting, either children visiting from house to house, singing a song and asking for money or food, or (as with our egg) a group of visitors congregating at one house. Roud records a song that was associated with this activity:

Here's two or three jolly boys all of one mind

We've come a-pace-egging if you will prove kind

If you will prove kind with your eggs and strong beer

We'll come no more nigh you until the next year

Fol de roodle di diddle dum day

Fol de roodle di diddle dum day

[Roud, 2006:119]

In some areas of England, painted Easter Eggs are rolled down steep hills on Easter Sunday. Another tradition was 'jarping' or 'egg-dumping', where a person held an egg in a cupped hand, and the other person used his egg to tap the other egg, the loser was the holder of the first egg to break. [Roud, 2006:120]

In most cases the traditional painted Easter egg was made by boiling the egg either with a dyeing product (such as onion skins or cochineal) or painted after being boiled or else by blowing the egg (piercing the egg at both ends, and blowing into one hole to remove the yolk and white at the other) and then decorating the shell with applied paint. Roud describes several methods of decoration including: marking a pattern with a tallow candle, then boiling with colouring so that a pattern appears with some areas, marked by tallow, left uncoloured; marking patterns in coloured eggs with penknives, colouring with onion skins, saffron, gorse flowers, and glueing white ribbons, tinsel and other items. [2006:120] In Victorian times he believes that decorating eggs was a complex craft and spread throughout the country by the late nineteenth century.

Several recipes are given at http://www.seaham.i12.com/sos/paceeggs.html:

"The eggs being immersed in hot water for a few moments, the end of a common tallow-candle is made use of to inscribe the names of individuals, dates of particular events, &c. The warmth of the egg renders this a very easy process. Thus inscribed, the egg is placed in a pan of hot water, saturated with cochineal or other dye-woods; the part over which the tallow has been passed is impervious to the operation of the dye; and consequently when the egg is removed from the pan, there appears no discolouration of the egg where the inscription has been traced, but the egg presents a white inscription on a coloured ground. The colour of course depends upon the taste of the person who prepared the egg; but usually much variety of colour is made use of.

"Another method of ornamenting 'pace eggs' is, however, much neater, although more laborious, than that with the tallow-candle. The egg being dyed, it may be decorated in a very pretty manner, by means of a penknife, with which the dye may be scraped off, leaving the design white, on a coloured ground."

(The Every-Day Book, 1827 re Cumberland)"We used to save onion skin, then boil it up in water and put the eggs in. They came out brown, but patterned as the shapes of the bits of onion skin pressed against them in the pan." (Croxdale)

"You could wind string round the eggs and boil them in water with cochineal. They came out with spiral patterns on them. Or wrap ferns round the egg for intricate patterns." (Seaham)

Hints: red cabbage, cocoa, and a number of similar common items can be used as dyes in the water. The appearance is improved by rubbing the finished egg with olive oil.

Further reading

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_season

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sowing

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Good_Friday

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hot_cross_bun

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_egg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egg_decorating

http://www.seaham.i12.com/sos/paceeggs.html

Christina Hole. 1941-2. English Custom and Usage. London: Batsford

Mary Danielli 1951 'Jollyboys, or Pace Eggers, in Westmorland' Folklore vol. 62 no. 4 pp.463-7

Ronald Hutton. 1996. The Stations of the Sun: A history of the Ritual Year in Britain Oxford: Oxford University Press [especially pages 179-214]

Steve Roud. 2006 'The English Year: A month-by-month guide to the nation's customs and festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night' London: Penguin Books [especially pages 105-134]