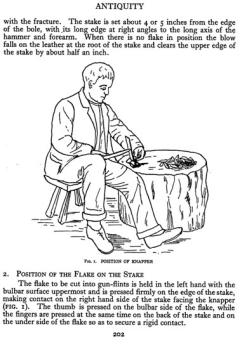

Figure 1: Manufacture of Gun-flints. Illustration shown with permission of Antiquity Publications Ltd

Professor Henry Balfour has informed the authors of an interesting observation made by him when watching the late Mr Fred Snare at work making gun-flints. He noted that Snare when trimming and removing irregularities from the sides and 'heels' of the gun-flint did so with a sideways, 'shearing', blow of the knapping hammer. [p. 206]

In conclusion the authors write:

The French knappers (now extinct) used a hammer head in the form of a thin disc which made a point contact on the flake, but they were unable to produce the undercut fracture by means of a single blow. They produced the undercut by removing a series of small flakes or 'gnawing' as the English knappers term it. Between 1838 and 1848 French gun-flints with their 'gnawed' edges and heels were sent to Brandon to be trimmed by the single-blow undercut fracture. The survival in England of this special form of technique may be added to the arguments adduced by Skertchly for the continuous existence of the industry at Brandon from Prehistoric times. [p.207]

An article with a similar name, Barnes, A.S. and Francis H.S. Knowles. 1937. 'Manufacture of gun flints' American Antiquity 11: 201-7 was also published.

Dr R.R. Marett , D.Sc. D.Litt. Rector of Exeter College, Oxford. - Western North America, Oregon of California. Black obsidian blade 61/2 inches long, 11/2 inches wide in middle, tapering to point at either end, worked all over w. obliquely fluted flaking. Found at entrance of University Parks opposite Keble College by Rector's grand-daughter, in October 1941, advertised by Penniman and Knowles in Man 1941.88 for one year.

Knowles and Penniman describe the artefact as 'black obsidian blade 6 1/2 inches long, 1 1/2 inches wide in the middle, tapering to a point at either end, worked all over on both sides with obliquely fluted flaking ... Usually the oblique flakes meet near the middle of the blade, but in at least one instance the flake has run right across its face. In two small areas on one of the lateral margins of the figured face, the flake run straight across to the middle, but elsewhere on that face the flaking is all oblique. The section is thin, the edges very sharp and unworn, the surface is in excellent condition, and there are no marks of abrasion or rough treatment. The point at one end is lost, but it is not clear whether this is a recent or an old injury. With this exception and a couple or so of small chips from the edge, the piece is in perfect condition.

They concluded that:

It appears likely from the material, shape, and flaking technique, that the blade is an American Indian knife from Western North America (Oregon or California). A piece of a similar specimen is in the Pitt Rivers Collection, labelled '?Mexico' but another obsidian knife from Mexico in the collection is characterized by a square base and a beautifully fluted flaking straight across from the lateral margins ... the piece is in perfect condition, as perfect as the ceremonial blades from California described by Frances Watkins in The Master Key (September, 1939) blades which were carefully wrapped in redwood bark and hidden between ceremonies'.

The authors proceed to review the similar artefacts in the Museum's collections. They note that 'the blade found near the Parks is noteworthy for the exquisite workmanship of the oblique flaking'.

It is clear that not only did Knowles bring his vast knapping experience but also his North American knowledge to identify this piece. As can be seen from the accession book entry, the blade is accessioned as if it is definitely from North America. However, the short article does not address the most remarkable point, if the flake knife was truly from North America, how had it ended up in the University Parks, to be found by a child? An idea of what they thought is alluded to:

One side of the blade only is figured here. The other side has certain peculiarities which its owner will be able to describe if the blade belongs to any existing collection. It is proposed, if no rightful claimant appears within a year of publication, to retain the knife in the Pitt Rivers Museum.

So it seems that Penniman and Knowles believed that the blade might have been stolen from a private collection and lost (for some reason) in the Parks. Presumably they checked their own records at the Museum and at the Ashmolean Museum to confirm that it was not part of those collections! It appears that the 'rightful' owner did not appear as the blade was accessioned.

The 'peculiarity' referred to appears to be a matt section of stone towards the middle of the blade, which is clearly visible in the photograph shown here.

Thanks to Elin Bornemann and Matthew Nicholas for help and comments regarding this artefact.

Notes

[1] Victor Robert Edwards (1898-1963) was well known at the Pitt Rivers Museum. By the twentieth century, it was difficult to earn a living as a gun-flint manufacturer (unsurprisingly) so Edwards made reproductions for stone tool collectors. An account of Edwards working is given in H.V. Morton's In Search of England: 244-8. The Museum has many pieces made by him, donated by F.H.S. Knowles, including 1934.7.7-8, 1936.60.23, 1937.54.1-10, 1939.11.1-4, 1939.12.7-11, 1940.7.6, 1944.10.02-013, 1949.5.29-34, 2006.81.1-14 [the latter found unentered]